The present entry is a brief review of an original article entitled ‘Effects of hamstring-emphasized neuromuscular training on strength and sprinting mechanics in football players’ from Mendiguchia, Martinez-Ruiz, et al. (2014) recently published in Scand J Med Sci Sports. Link here.

Hamstring muscle strains are the most prevalent muscle injuries reported in football (soccer) (Mendiguchia et al., 2013) and the most of hamstring injuries occur while players are running or sprinting. During the stance phase of sprinting, hip extensors (including hamstring) muscles seems to be crucial in producing horizontal forces to propel body forwards. In this sense, it has been recently shown that horizontal maximum theoretical force and power appear impaired after return to sport from a hamstring injury in football players (Mendiguchia, Samozino, et al., 2014). In Mendiguchia, Martinez-Ruiz, et al. (2014) a novel and training-ecological integration of commonly used injury prevention-oriented hamstring exercises with a training program targeting sprinting performance (i.e. acceleration) was shown. The effects of a 7-week simple, field-based neuromuscular training program, that combined posterior thigh eccentric-biased muscle strength, horizontal-focused lower limb plyometrics, and sprint training drills, in addition to regular football training on knee extension/flexion strength, sprinting performance, and horizontal mechanical properties of sprint running was examined during the study.

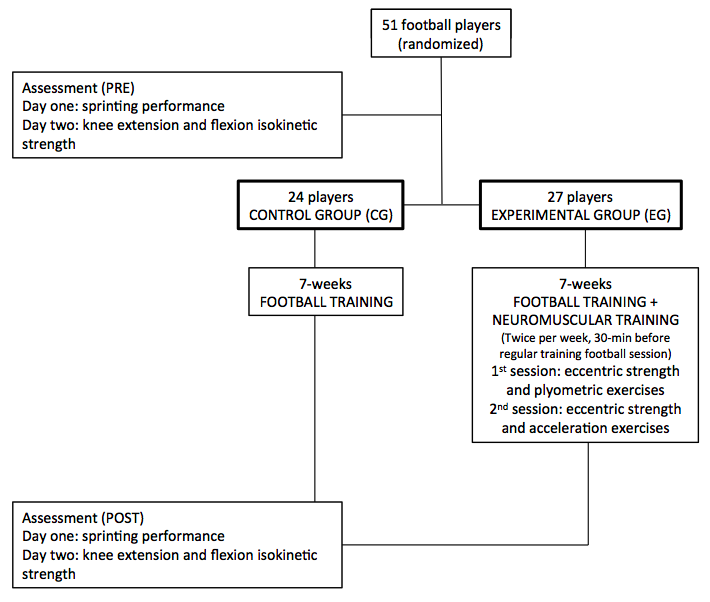

The methods of the study are summarized in Figure 1. The neuromuscular training program consisted in eccentric exercises (i.e. nordic hamstring, deadlift, hip thrusts forward lunges, etc.) plyometric exercises (i.e. broad jump, hurdle jumps, long strides, drop jumps [Figure 2], etc.) and acceleration exercises (free 5-10-15 m sprint, wall acceleration drills, weighted sled towing 5-10 m sprint, etc.) (for further information about the exercises included in the neuromuscular training programe see

here).

Interestingly, results showed that the EG presented small increases in concentric quadriceps strength (ES = 0.38/0.58), a moderate to large increase in concentric (ES = 0.70/0.74) and eccentric (ES = 0.66/0.87) hamstring strength, and a small improvement in 5-m sprint performance (ES = 0.32). By contrast, the CG presented lower magnitude changes in quadriceps (ES = 0.04/0.29) and hamstring (ES = 0.27/0.34) concentric muscle strength and no changes in hamstring eccentric muscle strength (ES = −0.02/0.11). Thus, in contrast to the CG (ES = −0.27/0.14), the EG showed an almost certain increase in the hamstring/quadriceps strength functional ratio (ES = 0.32/0.75). Moreover, the CG showed small magnitude impairments in sprinting performance (ES = −0.35/−0.11).

Figure 2. Example of one of the exercises included in the neuromuscular training program: lateral single-leg drop jump from 40 cm to horizontal single leg jump.

Based on the results exposed by (Mendiguchia, Martinez-Ruiz, et al., 2014), 7 weeks of hamstring–emphasized neuromuscular training combined with football training appear to be effective in improving concentric and specifically eccentric hamstring muscles strength compared with football training alone. In addition, greater hamstring compared with quadriceps strength improvement resulted in an increase in both the conventional and functional ratio, which may be advantageous to prevent or rehabilitate hamstring muscle strains. Sprinting performance was typically maintained, with a slight improvement observed in 5-m sprinting speed, in the EG while the CG showed some small magnitude declines in most of the sprinting speed parameters analyzed. These results indicate that a neuromuscular training program, in an ecological and real football team context, can induce positive hamstring strength and maintain sprinting performance, which might help in preventing hamstring strains in football players.

With no doubt, the cited study (Mendiguchia, Martinez-Ruiz, et al., 2014) brings new insights into both sprint (acceleration) performance and hamstring injury prevention in football players.

References:

- Mendiguchia, J., Arcos, A. L., Garrues, M. A., Myer, G. D., Yanci, J., & Idoate, F. (2013). The use of MRI to evaluate posterior thigh muscle activity and damage during nordic hamstring exercise. J Strength Cond Res, 27(12), 3426-3435. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31828fd3e7.

- Mendiguchia, J., Martinez-Ruiz, E., Morin, J. B., Samozino, P., Edouard, P., Alcaraz, P. E., . . . Mendez-Villanueva, A. (2014). Effects of hamstring-emphasized neuromuscular training on strength and sprinting mechanics in football players. Scand J Med Sci Sports. doi: 10.1111/sms.12388.

- Mendiguchia, J., Samozino, P., Martinez-Ruiz, E., Brughelli, M., Schmikli, S., Morin, J. B., & Mendez-Villanueva, A. (2014). Progression of mechanical properties during on-field sprint running after returning to sports from a hamstring muscle injury in soccer players. Int J Sports Med, 35(8), 690-695. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1363192.

Ваш средство объяснения всего этого

в этой абзаце – это хорошо, все могут просто

понять это, спасибо большое.